|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

That goal requires engaging the world. Andrés Duany points out that architects are often satisfied within their ivory towers, flying beautiful banners and refusing to muddy themselves in sprawl and inner-city struggles outside their walls. New Urbanists have fought the good fight instead. So that today, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development tears down what Jane Jacobs called "urban removal" projects and replaces them with traditional neighborhood developments. The governor who heads the National Governors Association and the mayor who runs the U.S. Conference of Mayors are New Urbanists. And the magazine for the National Association of Homebuilders said five years ago, in their "What’s Hot And What’s Not" section, "Say you’re neo-traditional even if you’re not." CNU member Harriett Tregoning founded and funded the smart growth movement at the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, which later made Atlanta the Smart Growth capital of America by taking away its highway funding. CNU founder Peter Calthorpe forged alliances with environmental groups like the Sierra Club, which today is one of the most effective advocates of urbanism in the United States. These are successes very few people would have predicted 10 years ago. Ironically, some of the biggest failures of the CNU come in the area where it is supposed to be the strongest: in the making of beautiful places. The CNU’s critics say that’s all New Urbanists care about, but getting TNDs built is a long and complicated process, with many compromises along the way. Many CNU members are unhappy with the quality of the places that have resulted. This reaction is both idealistic and pragmatic. New urban designers idealistically strive to make the best places we can (we are designers, after all, because we respond to good design). And we realistically acknowledge that the most important factor in public acceptance of New Urbanism has been the successful completion of good models. In the 1980s, I was part of an early Duany Plater-Zyberk charrette in which the developer participated in a serious debate about the ethics of chimney construction. The essence of the debate was this: If the chimney was bricked where it showed above the roof, was it necessary to have load-bearing brick construction all the way down to the ground, even though the bricks would be inside the walls where no one could see them? Or was it acceptable to have load-bearing construction using concrete blocks in those situations? None of the young architects realized that 10 years later, one of the new DPZ partners would build his own house in Kentlands with a button vent on the exterior wall of his house for his gas fireplace. Because that was what he and most of his neighbors at Kentlands could afford. Nor did we realize how much our design ideas would change as we worked with national builders like Pulte and Toll Bros. In 1998, I made a short trip with Rob Steuteville, the editor of the New Urban News. In the middle of visiting five New Urban projects in two days, Rob suddenly said, "You know, sometimes visiting these projects really gets depressing. When I started the New Urban News five years ago, I thought we’d be a lot farther along by now. But on a scale of one to 10, I can’t give this project more than a three." The next day we saw a town-center project under construction that Rob liked a lot more: "I’d give this a seven," he said. "If this is a seven, the Campidoglio is a 27," I said. "You can’t compare a new urban commercial development to a Roman piazza!" he said with exasperation. But New Urbanists know how simple some of the most beautiful Italian piazzas (or best New England villages) are and how simple it should be to make something as good. There are many reasons why we have yet to equal the quality of a good American small town or city street from a hundred years ago, and often the least of those is design. One is our contemporary building culture, which has very low standards and a great deal of confusion about what makes a good place. Another is the mass of building and planning regulations, which apply generic, autobased suburban standards virtually everywhere in the country, regardless of whether they are being used in an old downtown or the middle of a forest. Again, we have an ivory tower problem. At the first congress, Michael Dennis advocated that New Urbanists build only in the city, leaving the suburbs, and thereby 90 percent of everything built today, to others. But we will never reform America if we refuse to leave our noble fortress, thinking that our beautiful banners will be enough to make others forsake developing thousand-acre subdivisions. How can New Urbanists work with Pulte Homes and Toll Brothers without giving up the possibility of the best? To answer that, I would like to look at a concept I learned in a different type of design, furniture design. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

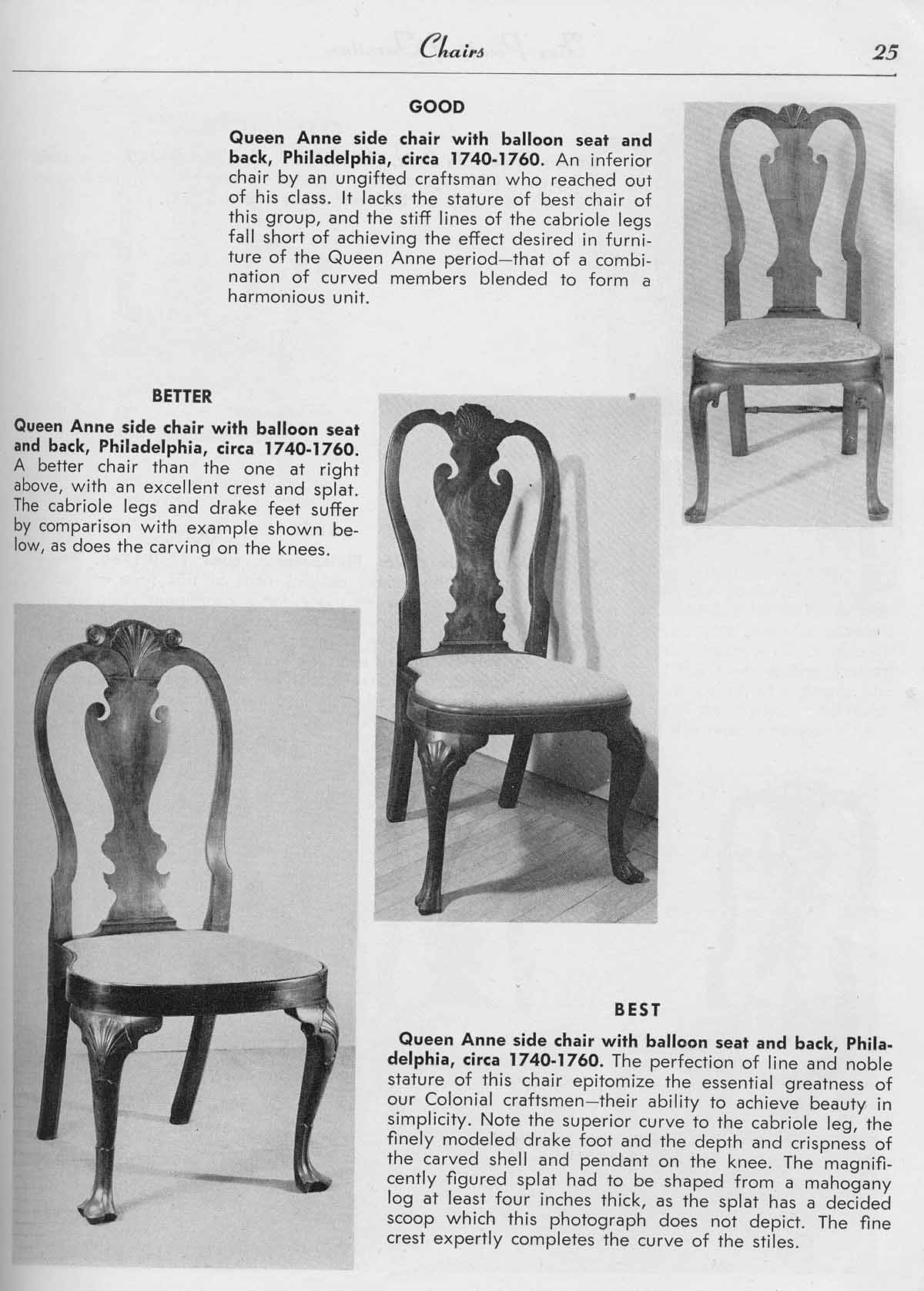

A Page from Israel Sacks's "Good, Better, Best"

The concept is a way of grading things qualitatively, as Good, Better or Best. I first heard of Good, Better, Best when I owned a store called America’s Best Traditional Designers and Craftsmen. From my architecture practice, I knew a number of craftsmen who made wonderful traditional furniture, windows and paneling, and other types of cabinetry and woodwork. I also knew how difficult it was to find these woodworkers — who usually worked out in the country somewhere — and how much more exposure greatly inferior craftsmen had. So I started a store to sell their work.

Once I was selling 18thcentury- style American furniture, I had to learn more about it, and I learned all sorts of things I heard about in architecture school. That included the secrets of traditional finishes, the qualities of various woods, how traditional joinery differed from contemporary practice, and knowledge of how construction details varied from region to region. I went to museums and looked at the best American furniture collections, which trained my eye to see subtleties I hadn’t noticed before then. And I found lessons that applied to the design of architecture and urbanism. The dimensions of the 18th-century chair embodied hundreds of years of experimentation. By 1700, chair makers had discovered the proper angle for the back, the perfect height for the seat, and the ideal depth for a cushion that would support the leg without cutting off the flow of blood behind the knee. Chair makers perfected the form for the comfort of the human body and then used that form to make supremely beautiful art from functional objects. Sheraton chairs, Chippendale chairs and Hepplewhite chairs all had the same basic dimensions, and yet they looked very different because both their forms and their elaboration were very different. The chair makers knew where to put their energies in making those elaborations. All the best chairs had several carvers working on them: The best carver would work on the top rail, the next best would work on the carving around the seat, and the apprentices would carve the feet. Not because the feet were less important than the top rails, but because they were farther away from the eyes of the beholders. In 1951, the leading dealer of 18-century American furniture wrote an interesting article for Antiques magazine in which he ranked many pieces of antique American furniture as Good, Better or Best, and showed how to make those judgments. He later turned that into a book of the same name, which became one of the most influential books in the world of antiques. The criteria for the judgments were simple: 1) design and proportion, 2) construction and detail, and 3) materials and finishes. There are some obvious comparisons with the Modernist principles of architecture and urbanism, which swept away traditional design. Even though they invented "the science of Ergonomics," many of the Modernist designers who made furniture only paid lip service to the functional paradigms for the comfort of people sitting in their chairs. The proof is in the pudding: In the name of functionalism, superstar architects and designers like Mies van der Rohe and Charles Eames designed some of the most uncomfortable chairs in the history of the world. They were less interested in comfort than the expression of modern materials and industrial processes. Van der Rohe wanted to perfect the assembly process of chairs made with curved chromium tubing. Eames was fascinated by the manufacturing process for bending a piece of plywood. Both wanted to tackle problems like speeding up the mass assembly line, or how to make chairs that would stack efficiently for storage. Each wanted to create an unprecedented form that expressed their industrial age and individual creativity. That produced a very different result than the traditional values of Good, Better, Best, which judged objects not on the basis of their originality, but on the execution and elaboration of ideas and forms that had been proven to work. Enough looking at different examples of 18-century chairs trains the eye to see the differences and appreciate the distinctions that distinguish one from another: One sees immediately that while one Chippendale chair might have a pair of front legs with beautiful curves, another chair has legs that by comparison are only good. Similarly, one chair might have a beautifully carved top rail, but another might have even better carving. Put that all together, and you have a list of objective criteria for judging furniture. The same principles apply to architecture and urbanism. Traditional buildings and streets are judged not on their originality, but on the quality of their design and their execution of enduring principles distilled over time. Twentieth century architecture and urbanism rejected timeless principles of design for principles judged to be of the time. This was often done by turning traditional principles on their head, to create what Machado and Silvetti call "unprecedented reality." The search for novelty made the criteria for judging architecture and urbanism subjective, while the standards for judging traditional architecture and urbanism are comparative and objective. For example, within the various forms of classicism — Romantic Classicism, Palladianism, etc. — we can say which in each category are Good, Better or Best. This has many useful benefits. One is that you can teach the principles for making a good traditional building or street to anyone, so that the student does not have to be especially talented to reach the level of Good. With the looser standards of Modernism, only the most talented and inventive reach the level of Good. The exception is in a Modernism based on well-defined principles, as is taught at Cornell. But in this age of Eisenman and Koolhaas, that is rare. Another benefit is that when dealing with the contemporary building culture, we can have different standards for different clients. Pulte Houses gets the parti and materials that a budget for the Good level can support, while the high-minded developer of the Windsor, an expensive Duany Plater- Zyberk designed TND-like resort in Florida, gets a code for the Best. Pulte might be allowed to use the Windsor line (no relation) of wood substitute windows, while Windsor can be held to the highest window standards, with only wood (unclad) allowed. A large obstacle to improving the buildings in new urban developments has been the cost of quality materials and supplies. Most of the projects can’t afford the best supplies, and there is an enormous drop in quality from the best to practically everything else.  When dealing with window manufacturing companies, we can have one set of standards for the economy budget (Good), another for a better budget, and third for the highest budget (Best). If we can pull some of the largest manufacturers and builders up to the level of the Good, we will have accomplished a lot. Trying to raise the level of design and construction of the pseudo-traditional materials and supplies prevalent in the building industry today is one of the primary missions of the Institute for Traditional Architecture. When dealing with window manufacturing companies, we can have one set of standards for the economy budget (Good), another for a better budget, and third for the highest budget (Best). If we can pull some of the largest manufacturers and builders up to the level of the Good, we will have accomplished a lot. Trying to raise the level of design and construction of the pseudo-traditional materials and supplies prevalent in the building industry today is one of the primary missions of the Institute for Traditional Architecture.Implicit in Good, Better, Best is also a way to resolve Rob Steuteville’s problem: If we create a scale with Good assigned 1 to 10, Better 11 to 20, and Best 21 to 30, we can grade the 27 piazza on the same scale as the 9 TOD town center without disparaging the town center. There are also less obvious implications. Comparing Seaside to Celebration illustrates one of them. At Seaside, Duany Plater-Zyberk and Robert Davis proposed a regional, construction-based vernacular, while Robert A.M. Stern Architects, Cooper- Robertson & Partners and Urban Design Associates planned Celebration to be built with a stylebook. Thus Seaside has blocks with consistent building types such as Charleston houses facing each other across the streets, while Celebration intentionally makes every block and facing block have a mix of styles that are primarily confined to the massing and the front façade. This is partly, I think, because my old boss Bob Stern likes playing with style, designing one house with five elevations, for example. And perhaps partly because so much of Urban Design Associates’ work has been with inner-city clients who cannot afford traditional construction: Their traditional component is mainly in their urbanism and their facades. But more importantly, Seaside was built by private owners and small contractors, while Celebration was built by national "homebuilders." There was plenty of money to be made at Celebration, but most of the builders did not want to spend too much time thinking about their Product: a generic name that accurately reflects the amount of design time spent on the individual buildings. Achieving the streetscapes that were built at Celebration was an important achievement. It was enough to say that inside the houses the homebuilders would build a product their buyers would want. Celebration raised the standard for large-scale development in Florida, where there are only a few new projects that can be called Good. But if you drive from Celebration to Miami, for every 100 places you see along the way — new or old — Celebration is better than 99 of them. That’s something to be proud of. Sometimes, the perfect is the enemy of the good, and you have to decide what’s good enough. |

|||||||||

|

· Blog · Architecture · Urbanism · Books ·

Woodwork · Education · Resume · Previous Month Veritas et Venustas |

|||||||||